Written by: Melanie Trezise (PhD candidate and Research Assistant at the University of Sydney Law School, and former ANJeL Executive Coordinator)[forthcoming in Journal of Japanese Law (2021)]

Academic events in the first twelve months of the COVID-19 pandemic were almost universally united by cancellations and virtual substitutes. The hallmark Kyoto and Tokyo Seminars organised by the Australian Network for Japanese Law (ANJeL) with Ritsumeikan University Law School were no exception. For the first time since 2005, Japanese, Australian and other international students unfortunately missed the opportunity in February 2021 to attend Ritsumeikan campuses for 9 days of in-person intensive learning in Japanese law.

In order to provide continuity to the seminar program, ANJeL, together with the Japanese Studies Association of Australia (JSAA), and funded by a mini-grant from the Japan Foundation Sydney, elected to provide brief introductions to the Seminar topics as short-form video podcasts. These were conducted in interview format, which is an intentional nod to the co-teaching format of the Seminars, and many interview pairings will be familiar to attendees at previous Seminars.

The podcast series begins with a short introduction by ANJeL co-director Prof Luke Nottage (University of Sydney). It is followed by a fascinating overview by co-director A/Prof Leon Wolff (Queensland University of Technology) on the nexus between pop culture and the law in Japan. The early billing of this interview in the podcast series playlist available via YouTube is not an accident, and it is hoped that this will be a tantalising hook for the podcast audience. Wolff’s work addresses the core question of “does law matter?” in contemporary Japan by using pop culture, especially television dramas, as evidence that law does, in fact, matter. This acceptance permits a shift in the question to how law matters and in doing so, Wolff moves beyond cultural and rationalist arguments to emotional attitudes towards the law.

The subsequent interview with long-time supporters of the seminars, Ritsumeikan University professors Tetsuro Hirano and Chihara Watanabe, sets the comparative context that is at the core of the Seminars’ international setting. The interview, led by Nottage, provides a concise introduction for students to some historical and theoretical perspectives on Japanese law. It also generates a wide-ranging discussion that extends to ongoing outside and home-grown influences on Japanese law, as well as the impact of justice system reforms since 2001 on the number and availability of lawyers in Japan.

This discussion links neatly to the following interviews on the practice of Japanese law, focusing separately on mediation and arbitration, civil procedure, as well as the experience of practicing lawyers in Japan. With respect to mediation, Nottage is joined by Professors Kyoko Ishida (Waseda University) and James Claxton (Rikkyô University / Waseda University) to discuss mediation as an alternative option to court processes and the impact of formalising that process in Japan, which has somewhat paradoxically required the involvement of legal (or quasi-legal) practitioners with specialist skills. Claxton presents a compelling account of the present and future of the new Japan International Mediation Center in Kyoto (JIMC-Kyoto).

As for arbitration practice in Japan, Nottage interviewed Prof Tatsuya Nakamura (Kokushikan University), Prof Giorgio Colombo (Nagoya University, and past observer of the Seminars) and Asst Prof Nobumichi Teramura (University of Brunei Darussalam). Japan’s recent legislative reforms in this area of law are discussed, as well as Japan’s competitiveness on the international stage as a preferred forum for commercial arbitration.

Prof Yoko Tamura (Tsukuba University) provides her expertise on civil procedure and gradually shifting changes in Japanese civil justice in favour of improved timeframes for pre-trial proceedings, having a positive impact on courtroom practice. Prof Tamura also flags integrated electronic practices as a key pathway for further improvements in civil procedure, a theme that appears in the pandemic ‘bonus feature’ discussed below.

Representing Japan-based legal practitioners, Mr Jiri Mestecky (Kitahama Partners) and Ritsumeikan graduate Mr Yoshihiro Obayashi (Yodoyabashi & Yamagami) provide insights into the experience of working as international lawyers in Japan. Linking to the academic debate on culture as an explanation for Japanese law practice, Mestecky and Obayashi describe the important role of international lawyers in cultural interpretation, as well as the anticipated impact of further new rules relating to gaikokuhô jimu bengoshi (外国法事務弁護士; registered foreign attorneys at law) on the number of foreign lawyers in Japan.

Prof Kent Anderson (Australian National University and founding ANJeL co-director, who also helped establish the annual Seminars from 2005) and Prof Makoto Ibusuki (Seijo University, who also co-founded the Seminars when formerly at Ritsumeikan University) were interviewed by Nottage about their always-popular classes co-teaching Japanese criminal justice to an international student audience. This begins with asking why students feel “safe” in particular settings, then developing an innovative, holistic approach to place Japan’s striking conviction and confession statistics in a socio-cultural context.

Wolff’s interview with Prof Narufumi Kadomatsu (Kobe University) will be a crucial introduction for foreign students of Japanese law seeking to understand gyôsei shidô (行政指導; administrative guidance) and its limits. This was a difficult interview to edit with Kadomatsu’s excellent case illustration of ‘voluntariness’ in administrative guidance unfortunately not making the shortened cut. The longer versions of all interviews will remain available for ANJeL core institutions and Ritsumeikan teachers to use in the (physical, virtual or blended) classroom.

Regarding gender and the law in Japan, both Prof Kyoko Ishida and Prof Masako Kamiya (Gakushuin University) are separately interviewed by Wolff. Ishida’s personal experience as one of only two tenured female law professors at Waseda University adds poignancy and immediacy to the discussion on women in legal education and practice, and the challenges that continue to be faced by women considering entering the profession. Kamiya’s interview provides the historical and contemporary context to the issue of gender and equal opportunity for women in Japan. We made the decision to break our own rules and present this as a ‘bonus’ long-form interview for the wider public, to permit drawing out some very important background issues that were impossible to cover within the standard format of 15-20 minutes.

This discussion on gender flows into Wolff’s interview with Prof Takashi Araki (University of Tokyo), particularly on the much-cited workplace practice of lifetime employment in Japan. Araki’s insight into the changing trends and demographics in different employment practices (including burgeoning ‘irregular work’ examples of fixed contract labour, part-time work and agency labour) will be thought-provoking for viewers, even those not usually interested in or familiar with labour law and practice.

On contract law, Prof Veronica Taylor (ANU) and Prof Tomohiro Yoshimasa (Kyoto University), in interview with Nottage, present some surprises for Australian businesses and students of contract law, in particular in relation to an illustrative case on the termination of a wine industry contract. They reflect on how contract practices in Japan have changed in recent times, including an increase in documentation of contracts in large enterprises compared to continued informal contracting practices of small- to medium- sized enterprises, which lack the same resources.

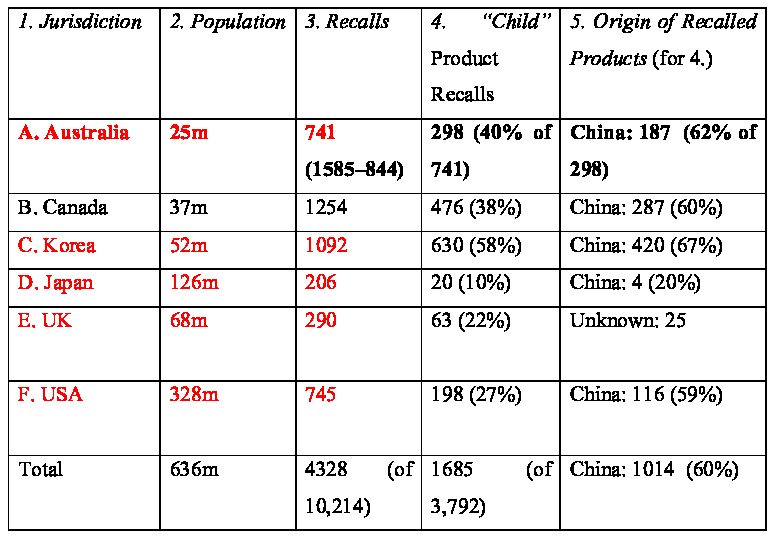

Prof Marc Dernauer (Chuo University) and Nottage discuss consumer law, in particular the complexities of consumer contract and consumer law regulation in Japan. Dernauer highlights the layered public law / private law dichotomy as a surprising feature of Japanese consumer protection following legislative reform in this area especially over the past few decades. As their discussion reveals, strengthening ex post relief for consumers through private law remedies and better access to dispute resolution services, in line with the 2001 justice system reform program and earlier deregulation, has arguably not led to much unwinding of ex ante public regulation aimed at protecting consumers more directly.

The discussion by Prof Akihiro Wani (Morrison & Foerster, Sophia University) on finance and the law, interviewed by this author, has a certain prophetic feel. This is particularly so with respect to rapid changes anticipated as a result of new types of brokerage products, especially given that this interview was filmed at the end of 2020, prior to the GameStop trading controversy.

Tax law specialist and ANJeL Program Director (Teaching and Learning), Micah Burch (University of Sydney), also supported the project by conducting two interviews. His tax law interview with Dr Justin Dabner (formerly James Cook University) reflects on the experience of teaching comparative tax law in Japan, as well as the globally relevant issue of carbon taxation. Burch’s second interview, with Kyoto Seminar graduate Dr Matt Nichol (Central Queensland University), discusses Japanese and international sports law. This is the only interview topic in the podcast series that is not a regular feature of the Kyoto and Tokyo Seminars. Not unlike a demonstration sports event at the Olympics, Nichol whets the appetite for this to be included in the Seminar series in the future by delivering a fascinating bonus feature worthy of a wider audience.

In addition to the above, many of the interviews also draw out preliminary observations on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to including edited versions of these responses in the main feature interviews, we made the decision to create a compilation of these observations into a joint bonus feature to permit immediate comparison of the answers relevant to different areas of law and society. Many answers reflected on the role of technological solutions to continue the practice of law in as ‘business as usual’ manner as can be approximated. The inability to file court matters electronically was a frequent theme and it will be interesting to see whether virus containment measures in Japan will accelerate this change in Japanese judicial practice.

Finally, the pandemic challenge was also discussed in Nottage’s interview of Professor Naoya Yamaguchi (Ritsumeikan University, current co-organiser of the Seminars), Wolff and Anderson. They also reflect more generally on the past, present and future of the unique Kyoto and Tokyo Seminar program. As Wolff explained in this concluding bonus podcast, “continuity and change” has always been a major theme for this innovative and educational series. That is also now a fitting theme in considering the format of the Kyoto and Tokyo Seminars themselves in the context of the ongoing global pandemic.

Indeed, in-person academic conferences and seminars are much more than just opportunities for self-funded students to fill up on catered sandwich triangles and norimaki – they have an essential role in providing opportunities for people to network and get a sense of everyday life in a different socio-cultural context. Most people will agree that this has proven challenging to replicate online, at least to establish new relationships and deepen perspectives. On the other hand, digital format conferences have provided a greater degree of accessibility, as demonstrated by the inclusion of these videos on YouTube for access by the general public.

It seems certain, however, that when they can return, and in whatever format the program must take, there will be a ready audience for ANJeL’s Kyoto and Tokyo Seminars co-hosted with and at Ritsumeikan. In the meantime, this podcast series delivers thought-provoking material for students, academics and practitioners alike, as well as a kind of time capsule for this broad community of people interested in Japanese law in a global context.