[Some of the background below is included in my posting on the Kluwer Arbitration Blog on 15 September 2024 entitled “Aggravating Australia’s Arbitration Ambivalence: Zeph’s ISDS Claims“. I conclude:

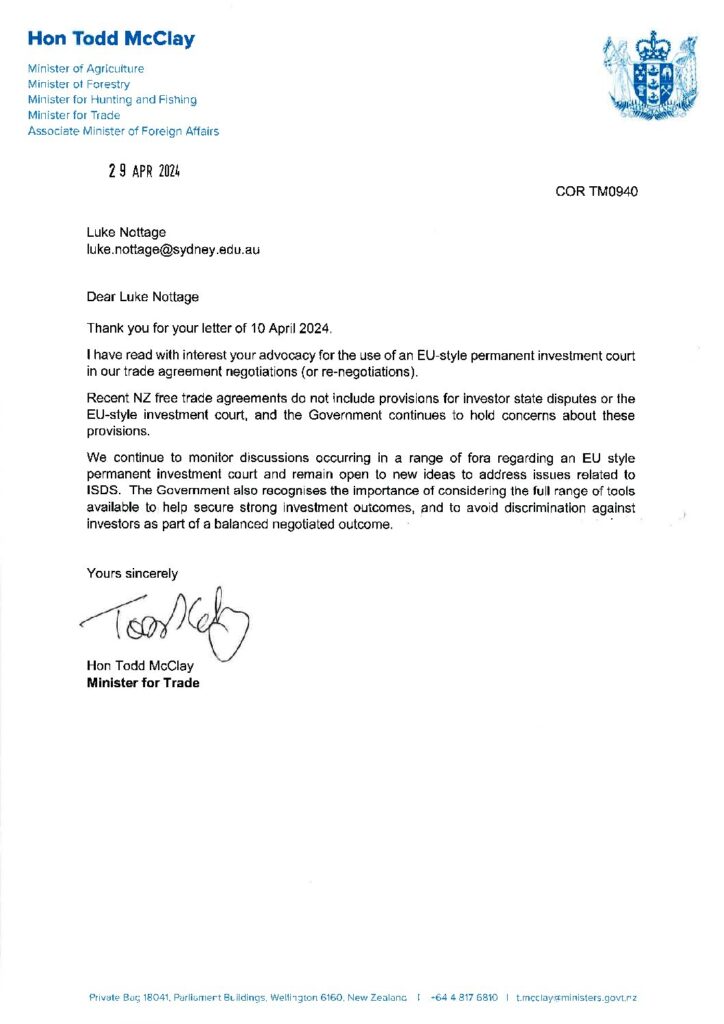

“… Overall, the Zeph claims against Australia, as well as parliamentary inquiries into ratification of IIAs like AANZFTA’s Second Protocol, are therefore likely to aggravate rather than assuage concerns in Australia over ISDS rekindled by the Labor Government’s new policy. This is despite tribunal rulings like those mentioned at the beginning [of the Blog posting, on interim measures], and considerable transparency in these multiple forums. Governments and stakeholders therefore need to work harder to promote productive debate and seek workable ways forward. An EU-style investment court or key features can be a useful discussion point for Australia and its counterparties to IIAs.”

***

The opportunity for nuanced public debate about Australia’s Labor Government’s late 2022 reversion to eschewing ISDS, and my proposed compromise of an EU-style investment court alternative process or key features thereof (such as a standing panel of arbitrators or an appellate review mechanism), is complicated politically by a succession of ad hoc arbitration claims brought by Singapore-incorporated Zeph. Controlled by Clive Palmer and his subsidiaries based in Australia, Zeph has filed several claims since 2023 under the 2021 UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, pursuant to the investment chapter of the original AANZFTA (signed in 2009) rather than the Second Protocol agreed in 2022 and expected to be ratified by Australia from mid-2024 (after the positive recommendation from JSCOT’s inquiry in which I gave evidence). Those objecting to retaining ISDS in the Protocol, albeit subject to a Work Program where the states party agreed to review whether ISDS should be retained, highlighted these Zeph claims. However, the JSCOT Report did not specifically mention the claimant, and its links to Australian mining magnate and former right-wing politician Clive Palmer.

The first Zeph v Australia arbitration claim (commenced on 29 March 2023) impugns Western Australia legislation enacted in 2020 (unsuccessfully challenged under Australian constitutional law) interfering with rights awarded to his subsidiary Mineralogy in 2002 regarding an iron ore project, as confirmed by two commercial arbitration awards. By preventing also access to judicial and administrative review, the claim appears strong on the merits, as elaborated in a publically available Notice of Dispute of 14 October 2020 (albeit under the Singapore-Australia FTA) evoking breach of fair and equitable treatment, non-discrimination and other protections. However, the jurisdictional objections are significant. Was Zeph incorporated in Singapore (seemingly in 2019) when the dispute was “reasonably foreseeable”, so the tribunal loses jurisdiction under customary international law due to abuse of rights, under the test applied and found to be made out in Philip Morris Asia v Australia? Can Australia further invoke the ‘denial of benefits’ Article 11 in AANZFTA’s Investment Chapter 11, as Zeph is controlled by an Australian and arguably has “no substantive business operations” in Singapore?

Accordingly, interesting legal and factual arguments are expected in hearings scheduled for the week of 16 September 2024 (under Procedural Order No 1), for the arbitration with the seat decided by the tribunal to be Geneva (contrary to Australia’s preference for London as seat). These hearings may take place at the seat in Geneva. However, as the agreed repository for documentation in this first Zeph case is the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague, parties and the tribunal may instead decide to request use of the PCA’s well-appointed hearing rooms.

Procedural Order No 3 (issued 19 January 2024), setting out transparency in most aspects for this first arbitration, interprets AANZFTA Chapter 11 Article 26.3 to make public such hearings and their transcripts (unless a party seeks and justifies confidentiality around certain information). Paragraph 15.iii of the Order adds that the parties’ “main written submissions shall be published on the PCA website at the end of the hearing to which they relate, subject to any prior redactions” of confidential information).

Procedural Order No 2 largely rejected various interim measures applications by Zeph, including curiously that the JSCOT chair stop making public statements impugning ISDS generally. But some of these applications might be revived (if for example Western Australia invokes indemnities against Palmer and his interests, pursuant to its 2020 state legislation).

Secondly, the Zeph v Australia (II) arbitration impugns measures taken by the Queensland state government relating to a minerals exploration project of Palmer’s subsidiary Waratah Coal. The Attorney-General’s Department revealed to federal Parliament in mid-2023 that Zeph had initiated a second ISDS claim, reportedly by notice of dispute under AANZFTA on 21 February 2023 followed by a formal notice of arbitration on 29 May 2023, seeking around A$41 billion in compensation. The agreed repository for this arbitration is again the PCA in The Hague.

A decision of 26 September 2023, from the agreed Appointing Authority (PCA Secretary-General Dr Marcin Czepkelak) adds that the Notice of Arbitration includes alleged breaches of AANZFTA investment Chapter 11’s articles 6 and 9 (FET and expropriation) concerning the Queensland state government’s “decision to grant an environmental offset to a direct competitor of the Claimant over land in which the Claimant’s subsidiary had certain coal exploration permits”.

The Appointing Authority’s decision rejected Australia’s challenge to Zeph’s nomination of Geneva-based Charles Poncet as arbitrator, based on old proceedings involving in him in Italian courts. Other public sources had indicated that Australia nominated Prof Don McCrae (also for the first Zeph case, and earlier the Philip Morris Asia v Australia case) and that the presiding arbitrator is Laurent Levy (who works in the same Geneva law firm as Prof Kaufmann-Kohler, who is presiding arbitrator in the first Zeph case).

In late July 2024 three Procedural Orders from the Zeph II tribunal were also made available via the Zeph II arbitration’s PCA webpage. The first (dated 25 October 2023) sets the first hearing on preliminary objections as the week of 29 September 2024. Curiously, paragraph 10.5 observes that “In accordance with Article 25(4) of the UNCITRAL Rules, hearings shall be held in camera unless the Parties agree otherwise”.

By contrast, Procedural Order No 3 (25 June 2024) paragraph 2.3 adopts the identical reasoning of the first Zeph arbitration tribunal in the latter’s Procedural Order No 3 on Transparency: AANZFTA’s “Article 26(3) stipulates that information submitted to the Tribunal or to either Party shall be protected from disclosure to the public if specifically designated as confidential. A contrario this implies that, absent such a specific confidentiality designation, the information in the record may be disclosed to the public.” Consistently, later in the Zeph II tribunal’s Procedural Order No 3, paragraph 2.9 notes that the parties agreed to apply certain elements of the first Zeph arbitration tribunal including that: “Hearings (other than procedural conferences) shall be open to the public. … Transcripts of the hearings shall be made public, subject to the redaction of protected information. Sound and/or video recordings should not be made public.” Again, it will be interesting therefore to see from the hearings scheduled for the week of 29 September 2025 (in person or perhaps livestreamed, and via subsequent transcripts and submissions) what jurisdictional objections are raised by Australia, presumably very similar to those being raised in the first Zeph arbitration hearings (scheduled for a year earlier).

Paragraphs 1.3 and 1.4 further note in February 2024 the first Zeph arbitration tribunal had accepted Australia’s proposal to share information with the Zeph II arbitration tribunal, and that in March 2024 the parties agreed to adopt the first Zeph arbitration tribunal’s Procedural Order No 3 concerning procedures to protect any confidential information. Thus, despite there being only Prof Don McRae on both tribunals, there has been some alignment achieved and related procedural efficiencies achieved in the two parallel arbitrations. However, it seems regrettably inefficient for the same parties to hold hearings on presumably very similar jurisdictional issues in September 2024 and a year later, before partially overlapping tribunals.

In addition, Procedural Order No 2 (dated 28 March 2024) briefly notes Zeph’s withdrawal of its application for interim measures (filed 7 November 2023 before the Zeph II arbitration tribunal), on 12 February 2024. According to paragraph 2.1, that application seems largely to have requested measures similar to those sought in the first Zeph arbitration, but additionally asking the tribunal to order Australia ‘to refrain from granting any further environmental offsets or equivalent measures over land or property owned by the Claimant or its subsidiaries’. Zeph’s withdrawal, to avoid any hearing and decision, promotes efficiency as on 17 November 2023 the first Zeph arbitration tribunal dismissed or ruled premature the quite similar requests for interim measures.

Thirdly, Zeph v Australia (III) focuses on a Queensland Land Court judgment recommending against a coal mine application by Waratah Coal. This dispute includes allegations of bias on the part of its President Kingham, according to a Notice of Intention to Commence Arbitration (albeit again under SAFTA, dated 20 October 2023) that the Australian government has made public. There is otherwise little public information available yet about this case, including when the actual Notice of Arbitration was filed.

Overall, it is unfortunate that Notices of Dispute or Intention to Commence Arbitration and Notices of Arbitration, let alone Responses from Australia, are not uniformly made public. Such documentation, very important to understand the key factual and legal issues in the cases, is not mentioned in the Procedural Orders on transparency in the first two Zeph arbitrations, but those Orders do reason that the starting principle underlying AANZFTA is transparency.

In addition, it is noteworthy that the Zeph II arbitration webpage does not contain Terms of Appointment of the arbitrators, as for the first arbitration. There is also no decision on the seat in the Zeph II arbitration, but its Procedural Order No 3 ends by noting that it is Geneva. Perhaps Australia agreed to that after the first Zeph arbitration tribunal ruled as such in favour of Zeph, or a the second Zeph tribunal so ruled but did not give any reasons for the decision on the seat (as the UNCITRAL Rules, in Article 34(3), only require reasons for awards).