[This is the original draft for a posting that was significantly revised and published under a different title on 29 October 2020 by The Conversation, prompting also interviews/podcasts with ABC National Radio “Life Matters” on 5 November 2020 and “Counterpoint” on 14 December 2020. This work is related to my ongoing ARC-funded joint research project DP170103136 and a JCP article published earlier this year (manuscript on SSRN.com here). A version will be presented and then discussed in the 1 December 2020 webinar for the International Association of Consumer Law (pre-recording available here) and the Consumer Law Roundtable hosted this year by QUT on 3 December. (Last updated: 1 December 2020.)]

The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened our awareness of safety risks, but also the socio-economic costs needed to reduce them. Public health interventions can also collide with human rights and constitutional principles, and undermine state capacity. Australia’s policy-makers and regulators are still facing many difficult choices to manage this new disease.

In consumer law, they and peak NGOs like Choice have also been busy grappling with a range of pandemic-related issues. These range from hand sanitiser quality through to refunds for airfares and other travel services. Nonetheless, hopefully policy-makers can now get back to some unfinished business, as we learn to live with COVID-19 while praying for a vaccine or cure.

In October 2019 the Treasury released its Consultation Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) entitled “Improving the Effectiveness of the Consumer Product Safety System”. This was part of a suite of reform initiatives agreed after the 2016-7 review of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), which re-harmonised consumer rights and regulatory powers nationally from 2011.

The review’s Final Report and now the RIS considered adding to the ACL an EU-style “general safety provision”. European countries (such as the UK in 1987, then the EU from 1992), as well as Hong Kong, Macau, Malaysia (1999), Canada (2010) and Singapore (2011, partially), have introduced such a GSP. It was discussed in several earlier government inquiries, notably by the Productivity Commission in 2006 and 2008, but the Commission concluded that the ACL should try some other measures first. A GSP would require manufacturers and importers to ensure that they only supply safe consumer products, otherwise risk public law sanctions from regulators.

Choice found that many Australians wrongly assume we already have this requirement. Yet the ACL currently only allows mandatory safety standards to be set pro-actively for specific types of general consumer products (currently around 40, many involving higher-risk children’s products). These specific standards take a long time to develop, usually only after serious injuries or deaths particularly within Australia. A recent example is renewed efforts to introduce a mandatory standard around button batteries, after a third child died in July and the AFL withdrew thousands of bracelets in October 2020. Regulators can also issue bans (around 20) for products found unsafe, but this is an even more reactive response.

Also only after harm arises, manufacturers can be indirectly incentivised to supply safe products by harmed consumers potentially bringing strict liability compensation claims. But such ACL product liability claims, requiring individuals to prove a “safety defect”, are becoming proportionately fewer. Even large class action law firms prefer focusing resources on more straightforward and large-scale claims by shareholders against listed companies for misleading conduct.

The Treasury’s draft RIS invited public comment on various reform options and three perceived problems with Australia’s consumer product safety system. One problem was misunderstanding about the current ACL regime. A second was its largely reactive nature, impacting on regulatory interventions and supplier behaviour. A third was considerable harm from unsafe consumer products. The ACCC identified 780 deaths and 52000 injuries annually. It also estimated at least a $4.5 billion annual economic cost, assuming around a $200,000 “value of a statistical life year” for premature deaths and disability. There were also costs of $0.5 billion in direct hospital costs for governments, and further costs associated with minor injuries and consequential property loss. (These seem conservative estimates, especially as the US consumer safety regulator recently US$1 trillion costs annually for that country – although the methodology and assumptions for that estimate are not set out in the UNCTAD report.)

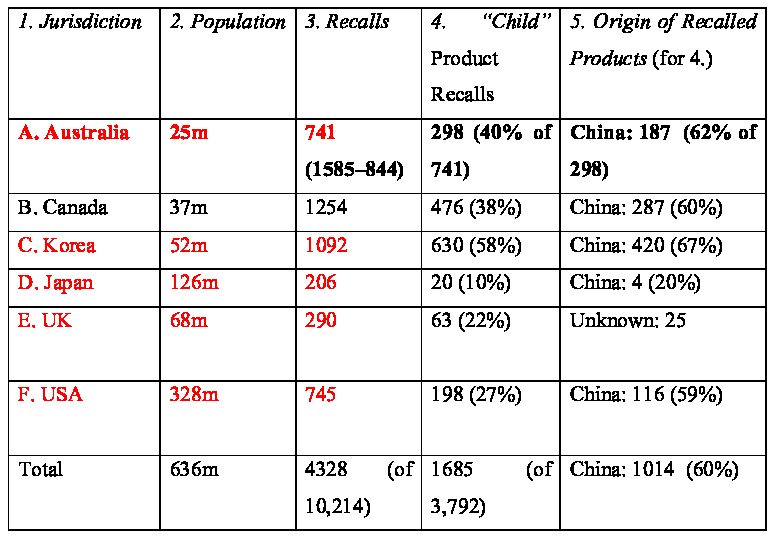

My own Submission and a related peer-reviewed article added comparative empirical data in support of a GSP. First, the OECD Global Recalls portal shows that Australia reported higher per capita voluntary recalls over 2017-9 than Korea, the UK, Japan and the USA. Australia reported a rate similar to Canada, at least on the OECD data, but Canada’s legislation has a more expansive duty on suppliers to report product accidents to regulators compared to that added to the ACL. A large proportion of our recalls involve child products, mostly from China.

[Table 1: Comparing Australia’s Recalls (2017-9)]

Secondly, annual recalls have been growing in Australia, as pointed out by Dr Catherine Niven et al (co-researchers for our ARC-funded project comparing child product safety) and various submissions by Choice. The uptick is noticeable from around 2012, tracking burgeoning e-commerce and more importers dealing with more manufacturers abroad. We can anticipate more more consumer product safety problems due to further online sales during the pandemic, and the ACCC issued warnings in April 2020. So far this year, though, annual recalls are down, according to the around 240 by end-October (excluding automobile recalls), compared to around 400 over all of 2019. This drop is likely to be temporary and caused by: (a) pandemic-related recession causing less consumer spending, (b) less time and energy for consumers to complain about unsafe products, (c) businesses struggling with finances and staff so not checking products and conducting or reporting recalls as much, and (d) less regulatory capacity to sweep bricks-and-mortar shops for unsafe products or monitor online platforms (except perhaps the larger ones).

[Figure 1: Australia’s Recalls (1998-2019)]

Perhaps for similar reasons, the Canadian government website shows a drop in recalls reported there this year too: about 130 by end-October compared to 251 over 2019. That website also curiously records fewer recalls annually for “consumer products” (excluding vehicles, foods and healthcare products) than reported on the OECD portal, suggesting Canada’s recall rate per capita may instead be significantly lower than Australia’s. Importantly, it shows a significant drop in annual recalls from 2009 (306) and 2010 (299) to 2011 (258) and 2012 (236), followed by annual recalls averaging around 250 consistently from 2013-2019. The GSP introduced by the Canada Product Safety Act 2010 therefore seems to have had a positive impact, shifting supplier mindsets towards adopting a more pro-active approach including better safety assessments before putting goods onto the market. Singapore also reported a drop in unsafe children’s products found there the year after it introduced a form of GSP through 2011 Regulations.

In further contrast to Australia, the USA reported significantly fewer recalls following the introduction of third-party conformity assessment for toy exporters after problems emerged particularly with China-sourced products around 2008. Dr Niven et al further note that Australian recall notices do not need to include some significant information, eg regarding (even de-identified) injuries. Many Australian recalls of child products also involve breaches of the mandatory standards that have actually been set. (For more details, see her PhD thesis now available here.)

Our regulators could try to sanction local suppliers more for such breaches. But introducing a broader GSP would encourage a “paradigm shift” needed among Australian firms. As discussed in my article, this ACL reform could complemented (but not replaced) by some of the other RIS options, and/or a “product safety substantiation notice” power (mirroring ACL s219, allowing regulators to require suppliers to substantiate claims or misrepresentations that might be misleading).

Introducing a GSP would make Australian suppliers think more carefully about (and document) safety assessments before putting consumer products on the market. This is more efficient and safer than releasing products and then trying to recall them after problems start to be reported, hoping not too many (more) consumers get harmed. It would also encourage Australian firms to “trade up”, like counterparts overseas, to the standards expected in many of our trading partners.

[Luke Nottage receives funding from the Australian Research Council: DP170103136, “Evaluating consumer product regulatory responses to improve child safety”. He provides occasional pro bono advice to Choice regarding consumer law and policy reform, and acknowledges assistance from them in compiling from government recalls data what is reproduced here as Figure 1.]