[Update of 4 December 2024: in my presentation tomorrow at the annual Australasian Consumer Law Roundtable, hosted by Deakin U in Melbourne’s CBD, I will present an updated version of my 2024 CCLJ article with Prof Souichirou Kozuka comparing consumer law administration, contracts and product safety. This will mention my Submissions (linked below) to three recent federal Treasury-led public consultations (perhaps prompted by a general election due by May 2025!) into (i) facilitating the Australian government adopting foreign standards for minimum safety of specific goods, (ii) adding civil pecuniary penalties for consumer guarantee remedies not provided by suppliers (including regarding safety, as an aspect of “acceptable quality” for goods), and (iii) a generic unfair commercial practices prohibition. Japanese consumer law has none of these features, but each raises interesting issues. Update of 6 January 2026: on the last-mentioned, see also my media commentary here.]

Yesterday (28 June 2024) I enjoyed attending the ACCC National Consumer Congress in sunny Sydney (program here). This annual invitation-only event provides an excellent opportunity to discuss cutting-edge law and policy issues with new and old colleagues working in Australian state and federal governments, consumer NGOs, businesses and academia (more limited, but I am pictured here with QUT’s Nicola Howell [expert in consumer credit, co-convenor of the academic-focused annual Consumer Law Roundtable] and Dr Catherine Niven [expert in product safety regulation, major contributor to my ARC Discovery Project on child product safety begun before the pandemic- with our last research output published in 2023 here] and Monash Em Prof Justin Malbon [co-author of my 2019 book on ASEAN Consumer Law Harmonisation, with UMelb Prof Jeannie Paterson who had to attend the Congress virtually this year]). It would be good to see more such events bringing together such stakeholders in Japan (compared with in my recent CCLJ article with Souichirou Kozuka), ASEAN and other Asian states.

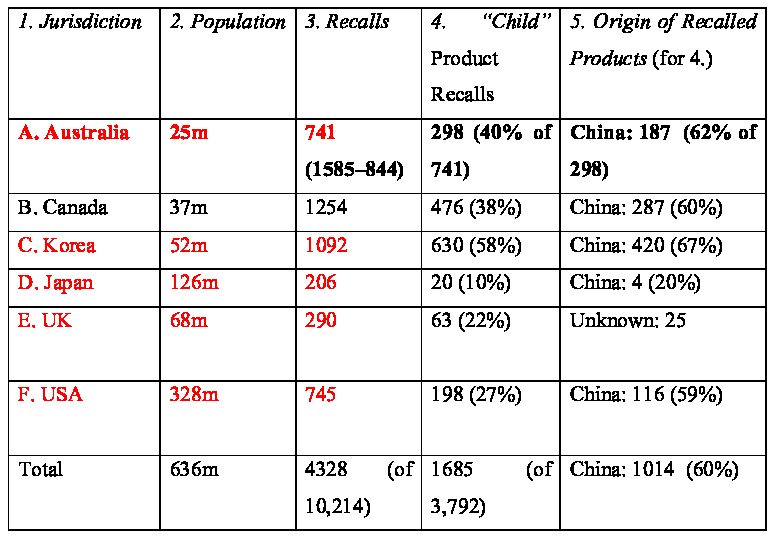

The first session was on “Buying in Australia – Are We Safe?”. The answer was “No” from panellists including Catherine (except perhaps one speaker). The opening speaker gave a moving account of how long and traumatic the process was to secure a mandatory product safety standard around button batteries, which were fatally ingested by her infant Bella. Another early fatality involving Britney was highlighted in my 2020 piece for The Conversation (leading to an ABC radio interview). That related also to my then Journal of Consumer Policy article arguing that the Australian Consumer Law did need to add an EU-style “general safety provision” (GSP) to fill gaps so suppliers switched to a more pro-active approach to risk assessments to ensure only safe consumer products were put onto the market, rather than waiting for accidents or risks to be identified and then conduct “voluntary” recalls of unsafe goods (mainly then only to avoid potential product liability claims for compensation and/or adverse reputational effects). In my comments at the Congress, I mentioned that after Canada added such a requirement in 2010, its recall rates went down; and when Singapore added a partial GSP (requiring all products to comply with EU, specified American or ISO standards) there were immediately fewer unsafe toys on their market. Yet the Treasury-led Consultation in 2020 into adding a GSP has led nowhere.

As alternatives, it seems, we find from late 2021 a further Consultation about allowing foreign standards to be adopted into the ACL (which I commented was a no-brainer) and another Consultation into allowing civil penalties for suppliers not providing remedies to consumers from defective – including unsafe – products under mandatory consumer guarantees (which I suggested was rather broad-brush and indirect, compared to ex ante regulation).

I also mentioned that unfortunately the written Submissions made by myself and others to all three Consultations have still not been made public. This is also true of the 2023 Consultation into adding to the ACL a general unfair trading prohibition (as under EU, US or Singaporean law). That would go beyond existing ACL prohibitions on misleading or unconscionable conduct to better address eg “dark patterns” facilitated by new technologies (such as “subscription traps” that the ACCC CEO reiterated at the Congress remain a concern). There were moves to make public Submissions to that Consultation (including mine, reproduced here for convenience and giving as an example such a subscription trap laid by The Economist magazine) and they were disclosed from 28 June (the day after the ACCC Congress) noting “79 submissions were received for this consultation, including 8 confidential submissions”. But in principle I believe such consumer law reform consultations should automatically make public submissions unless confidentiality is requested. That is now common good practice across Australian law reform bodies, including the Productivity Commission. In the same vein, Australia’s consumer law reform agencies should publicise at least a short report stating whether and why they may not be proceeding with ACL amendments.

I ended my comments by alerting Congress attendees to new developments in the EU that intersected with concerns raised by the panelists. The new General Product Safety Regulation requires suppliers to document product risk assessments (and implement traceability measures), notify regulators of progress on recalls, set up a public complaints portal (as the US has had for over a decade, but was not recommended in the 2017 ACL Review report) and make mandatory for online platforms some requirements (like responding within set time frames to complaints about unsafe products) that larger firms had adopted voluntarily under the 2018 EU Product Safety Pledge (mirrored by Australia’s 2020 Pledge). The EU Product Safety Pledge has itself been updated, and existing firms have re-signed it, to allow eg regulators to have access to the platforms’ portals to better monitor them for unsafe products.

The EU’s Product Liability Directive, which was adopted in 1992 has also recently been revised to better address new technologies and trends. For example, Article 7 makes an online platform jointly liable for harm if it suggests to an average consumer that products are provided either by the online platform itself or by a recipient of the service who is acting under its authority or control. However a recent comparative law article that Jeannie Paterson co-authored (and I helped with) noted a risk that platforms will avoid this liability potential by website and other disclaimers about exercising control over the suppliers. The article contrasts Californian cases against Amazon and other legal concepts that go further in imposing shared liability on such platforms, including pros and cons of such initiatives.

The second Congress session was on “Justice delayed: strengthening consumer dispute resolution in Australia”. Panellists highlighted persistent problems of access to justice, focusing initially on (prolific) defective vehicles and National Disability Insurance Scheme services. Although Prof Kozuka and I also highlight problems in Japan, I think Australia can do better in various ways. For example, because of the evidentiary issues raised in tribunals or magistrates’ courts, regulators should first more pro-actively use their ACL powers since 2010 to bring representative actions against suppliers who claim for example that cars or other complex products comply with the consumer guarantee of acceptable quality, such as reasonable durability. They can also support consumer NGOs who could run such test cases (eg to to determine how long a mid-value washing machine should last) and then publicise the outcomes, to help facilitate future negotiations and settlements.

Secondly, the NSW Office of Fair Trading should actually use its powers (added before the COVID-19 pandemic) to order suppliers to compensate consumers for up to $3000 in harm caused by products not complying with consumer guarantees, and publicise this among suppliers and consumers. Other jurisdictions should add such powers too, especially as the ACL is supported to be uniform across Australia. It is true that some suppliers may contest such orders. But they will also likely do that if and when the ACL adds powers for all consumers regulators to order civil pecuniary penalties for major failures, as mooted in late 2021 Consultation (paralleled by the Productivity Commission’s recommendations from an inquiry into Rights to Repair). Decisions from tribunals and courts, even at lower levels, will help clarify the meaning of general terms like reasonable durability.

Thirdly, we should introduce effective public complaints registers across Australia. Most jurisdictions lack them. And for example the NSW register does not differentiate by sales volumes or other measures of scale, making it hard for consumers or their advisors to determine if one supplier is really better or worse than others. These and other questions were raised in a 2017 Report by the Productivity Commission and should be revisited to improve access to consumer redress (and indeed informed purchasing decisions).

The third Congress session was on “Regulating for real people: understanding consumer behaviour to drive effective markets”. In his thought-provoking introduction (kindly shared now here), Consumers Federation of Australia chair Gerard Brody highlighted observed limits even with “nudges”, for example regarding electricity contract switching, and asked why suppliers shouldn’t just promise or be required to automatically put customers on the best plan. The CEO of (peak NGO) Consumers NZ pointed out that past consumption patterns may not be a good guide. I also wonder about handing over so much power and data to suppliers, and making consumers too passive (which is partly why for unfair contract terms regulation the price and subject matter cannot be impugned: consumers are assumed to be able at least to investigate and consider those, provided these items are not presented in a misleading way). A better solution might be electricity bills that say “if you switched to our Plan B you would save $XXX dollars” and then the customer could opt-in. [Update of 4 December 2024: after a recent problem with my electricity company in NSW, which had stated something like this on their bills but in a confusing way, I now am more amenable to Gerard Brody’s suggestion for an automatic “upgrade”.]

The Consumers NZ CEO provided an update on the progression of a private Member’s Bill to introduce a right of repair for New Zealand, including around spare parts availability, and likely mandatory labelling about durability (as recommended also by the Productivity Commission’s Right to Repair report). Again, I would add that the EU provides some good lessons for the antipodes (and say Japan). In February 2024 the EU institutions reached provisional agreement to enact the Right to Repair Directive, as part a larger environmental initiative aiming to extend a product’s life cycle and support a circular economy. Relevant features compared to the ACL regime (which for example allows the supplier not consumer to chose between repair and replacement):

“The Directive will require producers to carry out repairs outside of the legal guarantee for products covered by repairability obligations under certain EU ecodesign regulations listed in an Annex … [likely beginning with] certain white goods (including household washing machines, dishwashers and refrigerators), vacuum cleaners, electronic displays, and mobile phones and tablets (among others)

… [requirements for] information on certain spare parts to appear on a website, making them available to all parties in the repair sector and preventing certain practices that can hinder repair – including contractual clauses or certain software- and hardware-related barriers

… [seemingly] loan devices to be provided to consumers while they wait for repair in certain cases and to enable a consumer to opt for a refurbished unit as an alternative

… Under the existing Sale of Goods Directive, the seller is liable to the consumer for any lack of conformity which exists at the time when the goods were delivered and which becomes apparent within two years of that time. In the event of non-conformity, the Sale of Goods Directive sets out a hierarchy of remedies, allowing consumers to initially choose between repair and replacement … to encourage consumers to choose repair over replacement, the legal guarantee under the Sale of Goods Directive would be extended by 12 months following a repair …”.

This EU development also intersects with greenwashing, and the hot topic of the last Congress session – “Lightbulb moments: bold ideas to help consumers play a meaningful role in the green transition”.